What Is A Light-emitting Diode?

January 14, 2026

Read:268

Source: Ledestar

What Is A Light-Emitting Diode?

A light-emitting diode, commonly known as an LED, is a semiconductor device that converts electrical energy directly into light through a physical process called electroluminescence. Unlike traditional light sources such as incandescent or fluorescent lamps, LEDs do not rely on heating a filament or exciting gas plasma to produce light. Instead, they generate photons within a solid-state material, resulting in significantly higher energy efficiency, longer operational lifetime, and greater design flexibility.

Over the past several decades, LEDs have evolved from simple indicator lights into the dominant light source for general illumination, displays, automotive systems, horticulture, medical therapy, and a wide range of industrial and scientific applications. Understanding what an LED is requires not only a basic definition, but also insight into its historical development, internal structure, manufacturing processes, spectral characteristics, and real-world uses. This article provides a comprehensive overview of LEDs from a scientific and technological perspective.

The Historical Development of Light-Emitting Diodes

The history of the LED is closely tied to the broader development of semiconductor physics. The phenomenon of electroluminescence was first observed in 1907 by British experimenter H. J. Round, who noticed that certain inorganic crystals emitted light when an electric current was applied. At the time, however, the underlying physics was not well understood, and practical applications were limited.

In the 1920s, Russian scientist Oleg Losev conducted systematic studies on light emission from semiconductor junctions and published several papers describing the effect. Despite his pioneering work, the lack of suitable materials and manufacturing technology prevented LEDs from becoming commercially viable during this period.

The modern LED era began in the early 1960s with the development of the first practical visible-light LED. In 1962, Nick Holonyak Jr., working at General Electric, created the first red LED using gallium arsenide phosphide (GaAsP). This breakthrough marked the transition of LEDs from laboratory curiosities to functional electronic components. Early LEDs were relatively dim and expensive, limiting their use to indicator lights in electronic equipment.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, advances in semiconductor materials led to the development of LEDs emitting in additional colors, including green, yellow, and orange. Improvements in crystal growth techniques and doping methods gradually increased light output and reliability. However, the absence of an efficient blue LED remained a major obstacle to full-spectrum and white light generation.

A major milestone occurred in the early 1990s with the invention of high-brightness blue LEDs based on gallium nitride (GaN), developed by researchers including Shuji Nakamura. This innovation made it possible to produce white light either by combining red, green, and blue LEDs or by using blue LEDs with phosphor conversion. The advent of white LEDs triggered rapid adoption in lighting, displays, and numerous other industries.

Since then, continuous improvements in efficiency, thermal management, packaging, and cost have positioned LEDs as the dominant lighting technology of the 21st century. Today, LEDs are not only replacing conventional light sources but are also enabling entirely new applications through precise spectral control and intelligent system integration.

The Fundamental Working Principle of an LED

At its core, an LED is a type of p-n junction diode made from semiconductor materials. Semiconductors occupy an intermediate position between conductors and insulators in terms of electrical conductivity. By carefully introducing impurities, a process known as doping, engineers can control the electrical behavior of these materials.

In an LED, one side of the junction is doped to create an excess of electrons, forming the n-type region, while the other side is doped to create an excess of holes, forming the p-type region. When a forward voltage is applied across the junction, electrons from the n-type side and holes from the p-type side move toward the junction and recombine in a region known as the active layer.

This recombination process releases energy in the form of photons. The wavelength, and therefore the color, of the emitted light depends on the energy bandgap of the semiconductor material. Materials with a larger bandgap emit higher-energy, shorter-wavelength light such as blue or ultraviolet, while materials with a smaller bandgap emit lower-energy, longer-wavelength light such as red or infrared.

Unlike incandescent lamps, where most of the energy is lost as heat, LEDs convert a much higher proportion of electrical energy into visible or useful optical radiation. This fundamental difference explains the superior efficiency, low operating temperature, and long lifespan of LED devices.

Semiconductor Materials Used in LEDs

The performance and spectral output of an LED are primarily determined by the semiconductor materials used in its construction. Early LEDs were made from gallium arsenide (GaAs) and gallium arsenide phosphide (GaAsP), which are well suited for infrared and red emission. As material science advanced, new compound semiconductors were developed to cover a broader range of wavelengths.

Aluminum gallium indium phosphide (AlGaInP) is widely used for high-brightness red, orange, and yellow LEDs, offering excellent efficiency and stability. For green, blue, and ultraviolet LEDs, gallium nitride (GaN) and indium gallium nitride (InGaN) are the dominant materials due to their wide bandgap and high radiative efficiency.

The ability to precisely engineer these materials at the atomic level allows manufacturers to tailor emission wavelengths, efficiency, and reliability. This flexibility has been a key driver behind the rapid expansion of LED technology into specialized fields such as horticulture lighting and medical phototherapy.

LED Manufacturing and Packaging Processes

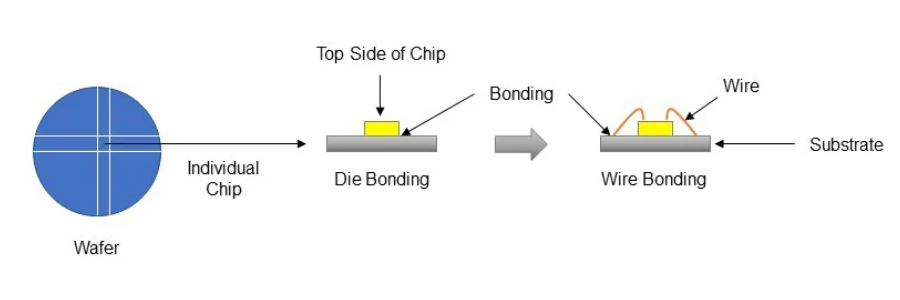

The production of an LED involves a complex sequence of material growth, device fabrication, and packaging steps. The process begins with the growth of high-quality semiconductor crystal layers, typically using techniques such as metal-organic chemical vapor deposition (MOCVD). These layers form the p-type and n-type regions as well as the active light-emitting layer.

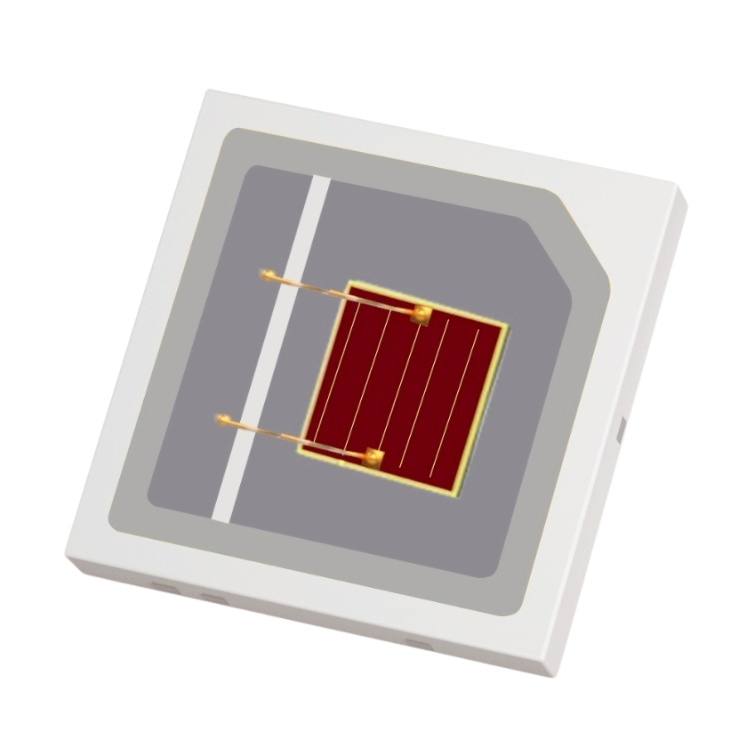

Once the epitaxial layers are formed, the wafer undergoes photolithography, etching, and metallization to define the diode structure and electrical contacts. The wafer is then diced into individual LED dies, which are microscopic chips capable of emitting light when powered.

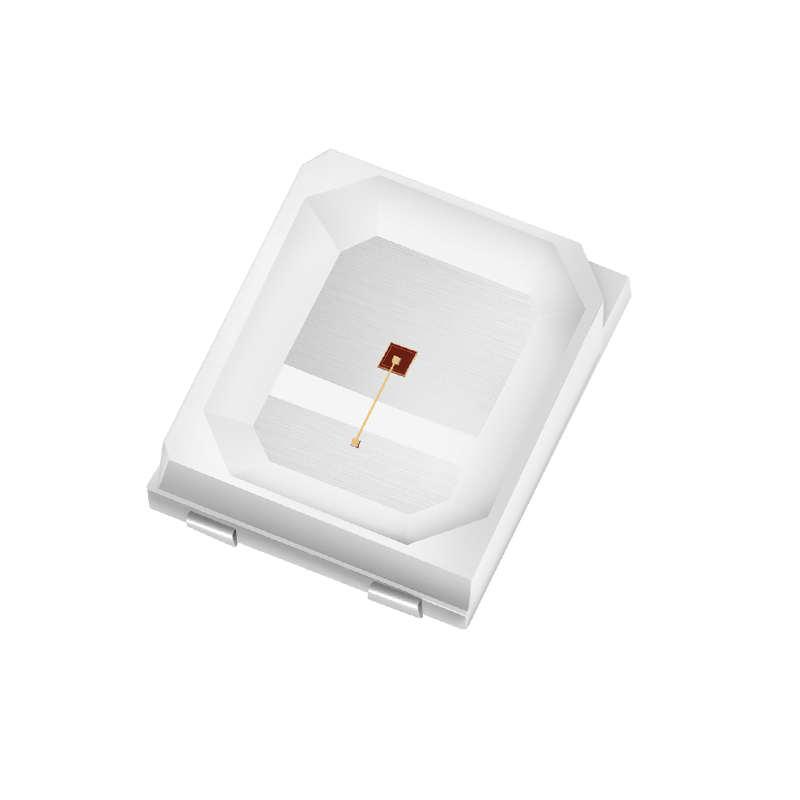

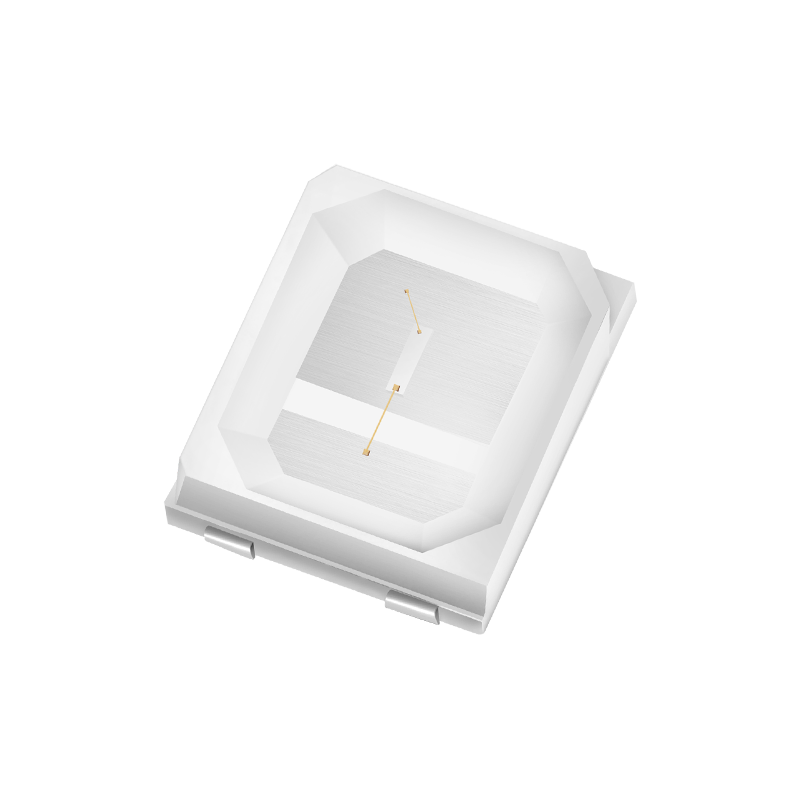

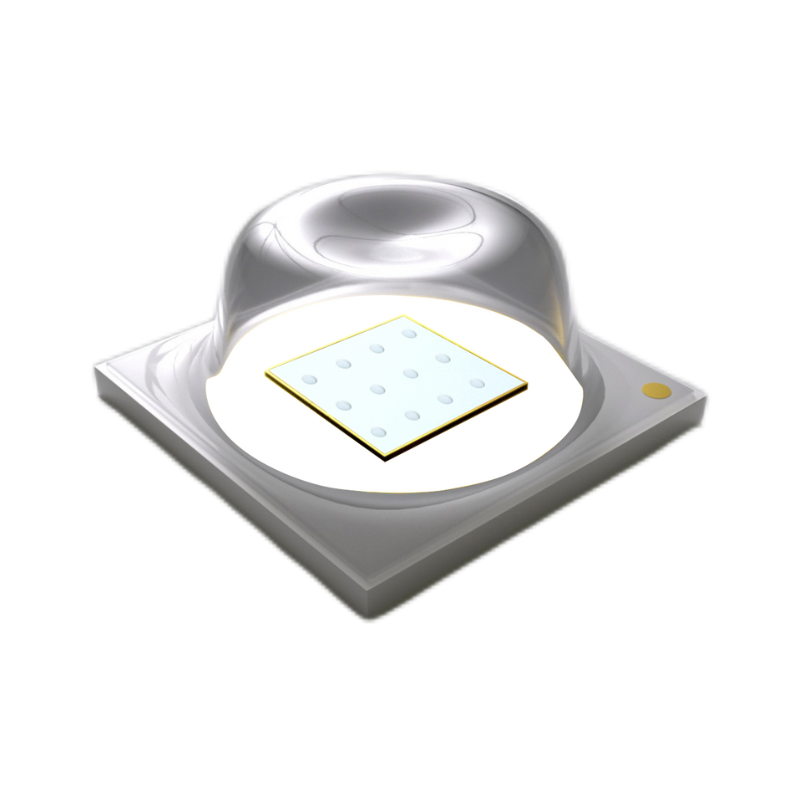

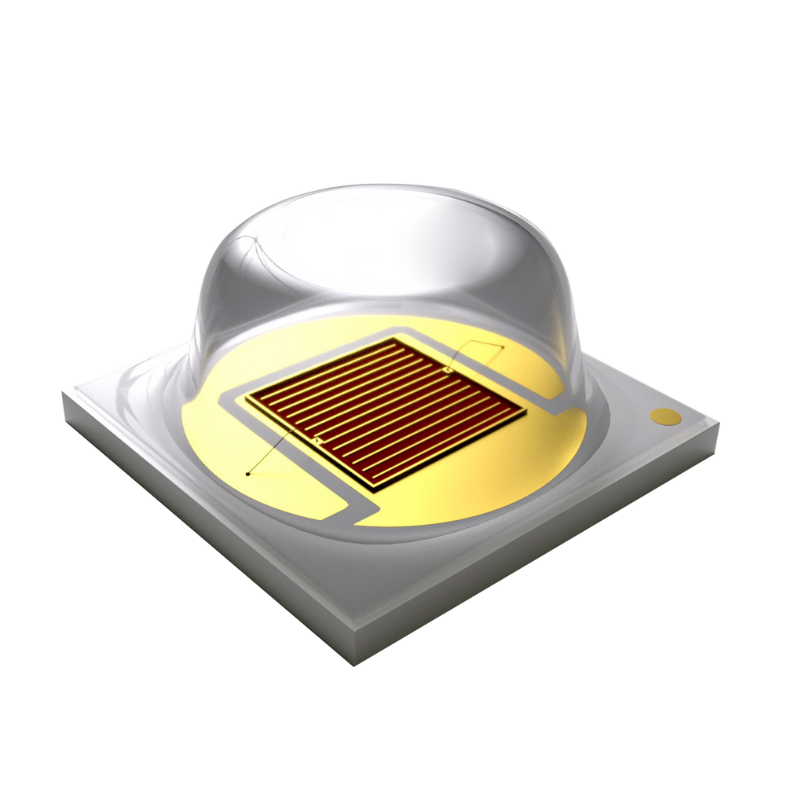

Packaging is a critical stage that determines not only mechanical protection but also optical performance and thermal management. The LED die is mounted onto a substrate, electrically connected via wire bonding or flip-chip technology, and encapsulated with transparent materials such as silicone or epoxy. In many cases, phosphor materials are added to convert the emitted light into a desired spectrum, particularly for white LEDs.

Different packaging formats, including surface-mount devices (SMD), chip-on-board (COB), and high-power modules, are designed to meet the needs of various applications. Advances in packaging have significantly improved heat dissipation, light extraction efficiency, and long-term reliability.

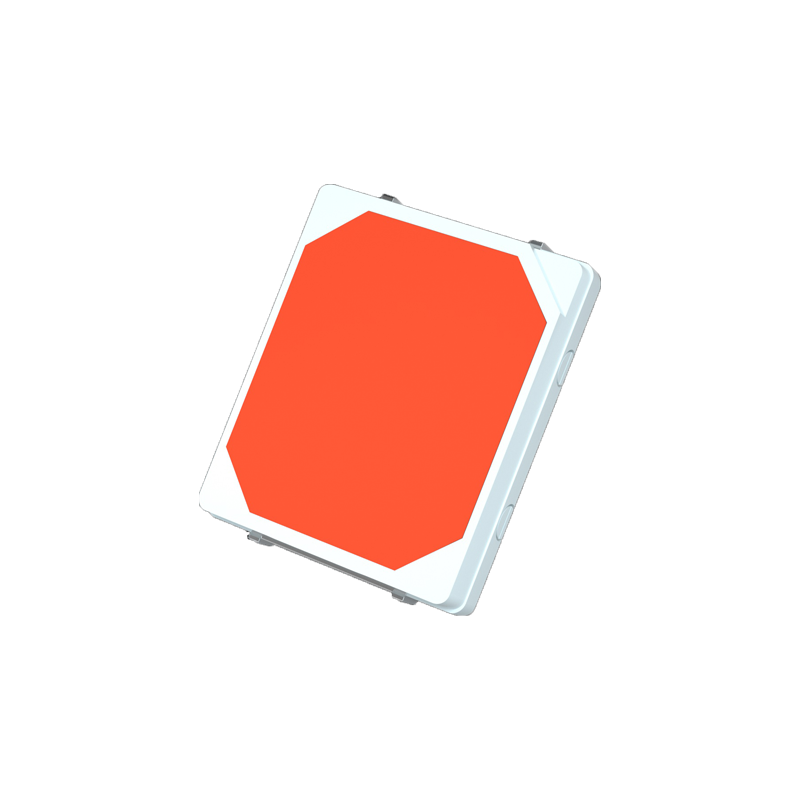

Ledestar LED Chip

SMD LED | |||

| SMD LED 2835 |  |  |  |

| SMD LED 3030 |  |  |  |

| SMD LED 3535 |  |  |  |

LED Wavelengths and Spectral Characteristics

One of the most distinctive features of LEDs is their ability to emit light at specific wavelengths with high precision. Unlike traditional light sources that produce broad, continuous spectra, LEDs naturally emit within relatively narrow spectral bands. This property makes them particularly valuable for applications requiring controlled light output.

Infrared LEDs, typically emitting at wavelengths above 700 nanometers, are widely used in remote controls, sensing, security systems, and medical devices. Visible light LEDs span from approximately 380 to 700 nanometers, covering violet, blue, green, yellow, and red light. Ultraviolet LEDs, emitting below 380 nanometers, are increasingly used for sterilization, curing, and analytical instrumentation.

White LEDs are usually produced by combining a blue LED with one or more phosphor materials that absorb part of the blue light and re-emit it at longer wavelengths. By adjusting the phosphor composition, manufacturers can control correlated color temperature (CCT), color rendering index (CRI), and spectral balance.

The ability to engineer LED spectra has opened new possibilities in fields such as plant lighting, where specific wavelengths influence photosynthesis and morphology, and in light therapy, where targeted wavelengths interact with biological tissues in distinct ways.

Applications of Light-Emitting Diodes

The versatility of LEDs has led to their adoption across an exceptionally wide range of applications. In general illumination, LEDs are now the preferred choice for residential, commercial, and industrial lighting due to their energy efficiency, long lifespan, and compatibility with smart control systems. Street lighting, office lighting, and architectural lighting increasingly rely on LED solutions.

In the display industry, LEDs serve as backlight sources for liquid crystal displays and as the fundamental pixels in direct-view LED screens. Their high brightness, fast response time, and durability make them ideal for televisions, smartphones, advertising displays, and large-scale video walls.

Automotive lighting represents another major application area. LEDs are used in headlights, daytime running lights, taillights, and interior lighting, offering improved visibility, design flexibility, and reduced power consumption compared to traditional lamps.

In horticulture, LEDs enable precise control of light spectra to support plant growth, flowering, and yield optimization. By tailoring wavelengths to plant physiological responses, LED grow lights provide higher efficiency and adaptability than conventional lighting technologies.

Medical and therapeutic applications are also expanding rapidly. LEDs are used in phototherapy for skin treatment, wound healing, pain management, and circadian rhythm regulation. Their ability to deliver specific wavelengths at controlled intensities makes them well suited for non-invasive medical devices.

Beyond these areas, LEDs are integral to industrial inspection, scientific research, communication systems, and consumer electronics. As technology continues to advance, new applications continue to emerge.

Advantages and Limitations of LED Technology

LEDs offer numerous advantages, including high energy efficiency, long operational life, compact size, and environmental friendliness. They contain no mercury, emit minimal heat in the forward direction, and are compatible with digital control systems. These characteristics make them an essential component of modern sustainable technologies.

However, LEDs are not without limitations. Thermal management remains critical, as excessive heat can reduce efficiency and lifespan. Initial system costs, while steadily decreasing, can still be higher than those of traditional lighting in some applications. Additionally, achieving optimal spectral quality and color consistency requires careful design and high-quality manufacturing processes.

Ongoing research and development continue to address these challenges, driving further improvements in performance and cost effectiveness.

Conclusion

A light-emitting diode is far more than a simple electronic component. It is the result of decades of scientific discovery, material innovation, and engineering refinement. From its origins in early semiconductor research to its current role as a cornerstone of modern lighting and technology, the LED exemplifies the power of solid-state physics applied to real-world problems.

By understanding the history, working principles, manufacturing processes, spectral characteristics, and applications of LEDs, one can better appreciate why this technology has become so influential. As research continues and new materials and designs are developed, LEDs will remain at the forefront of lighting and photonic innovation for years to come.

Table of Contents